What is an Automated External Defibrillator (AED)?

AEDs are life-saving medical devices that have been designed for use by non-medical individuals. Essentially, they are machines that you – or anyone – can use in an emergency where a cardiac arrest is suspected.

What is a cardiac arrest?

A cardiac arrest is where the heart has stopped beating normally, due to abnormal or absent electrical activity. It results in a lack of oxygen and prevents blood from being effectively pumped around the body.

It is fatal and can be irreversible in minutes, as a lack of blood and oxygen causes tissue death and brain damage.

A cardiac arrest is not the same as a heart attack, but lots of people get them confused. Read this blog to understand more about the differences between heart attacks and cardiac arrests and how to spot them.

Why are AEDs important?

In the UK, over 30,000 cardiac arrests occur outside of hospitals (72% in the home and 15% in the workplace) and half of these are witnessed by a bystander. Although CPR is attempted in 70% of cases, a public access defibrillator is reported as being used in fewer than 10% of cases.

CPR ensures blood and oxygen continue to flow around the body, delaying irreversible tissue death and brain damage, and helping to maintain a “shockable” rhythm for when emergency services arrive. However, in most cases, only defibrillation can restore the heart to normal and ensure survival. For every minute without defibrillation, the chances of survival drop by around 7-10%.

In January 2020, the London Ambulance Service published figures showing that out-of-hospital cardiac arrest survival rates were 58.1% when a bystander used an AED and delivered at least one shock. This is over five times higher than survival rates without defibrillation.

What does a defibrillator do?

AEDs are designed to detect fatal cardiac arrhythmia (abnormal electrical activity in the heart) and analyse a casualty’s heart rhythm. An AED will only issue a shock to someone who is both in cardiac arrest and who has a “shockable” heart rhythm that will respond to defibrillation. For a casualty who is in cardiac arrest with a shockable heart rhythm, the casualty is clinically dead and has no chance of survival without help.

It is not possible for the AED to issue a shock to someone who does not need it or wouldn’t benefit from it. Therefore, it is impossible for an AED to do harm to a casualty in any circumstances, making them very safe.

If a shock is required, the AED will command bystanders to avoid contact with the casualty when necessary. Should a casualty be in cardiac arrest with a non-shockable heart rhythm, the AED will direct rescuers to continue with CPR.

Not only this, all AEDs provide voice prompts throughout to instruct rescuers in how to use them.

How to use an AED safely

AEDs are safe for everyone to use, whether they are first aid trained or not. Once you switch an AED on, it will provide voice prompts instructing you through the process of preparing the casualty for defibrillation, applying the electrode pads and delivering the defibrillation shock.

The most important thing to remember is to stay calm in the situation. Being with an unresponsive casualty can be terrifying but the first few minutes are critical. It’s important to remember that the casualty’s chances of survival decrease hugely if you don’t attempt to help.

What to do if you're with an unresponsive casualty:

- ABC:

- Check their airways for any obstruction.

- Look, listen and feel for breathing.

- Check their circulation, e.g. are there any severe bleeds that may lead to shock?

- Call the emergency services immediately – if possible, get someone else to do this while you perform the ABC. If you are on your own, use the speakerphone function to allow you to continue administering care.

- If they are unresponsive and not breathing normally, begin CPR:

- Place the casualty on a firm, flat surface.

- Place the heel of one hand in the centre of the chest and place the other hand on top of the first.

- Compress the chest (maximum 5-6cm) 30 times at a rate of two beats per second. A common bit of advice is to do this in time to the song “Stayin’ Alive” by the Bee Gees.

- If you are trained in CPR, you should then stop to perform rescue breaths before starting the cycle again. If you are not trained in CPR, continue to provide chest compressions. You should not stop unless an AED arrives, someone else can take over, you are exhausted, or the emergency call handler tells you to.

- If there is a defibrillator, switch it on and follow the instructions. This will involve:

- Placing the defib pads on the casualty’s torso (directions on the pads).

- The defib will then analyse the casualty’s heart rhythm.

- The defib will then instruct you to stand back from the casualty while it delivers a shock, or it may ask you to press a button to deliver a shock yourself.

- You will then be asked to return to the casualty to perform CPR (see below)

- If there is no defibrillator, continue with CPR and send someone to look for a defibrillator (the emergency services will be able to give you a location). If you are on your own do not leave the casualty to look for a defibrillator.

Automatic and Semi-Automatic AEDs

There are two types of AED: semi-automatic AEDs and fully automatic AEDs. Both these types of AED will provide voice prompts to the responder and will only allow a shock to be delivered if one is required.

However, semi-automatic models will inform the user if the casualty requires defibrillation and, if so, will instruct the user to press a “shock” button. Whereas fully automatic models do not require the user to press any buttons to deliver a shock; if the AED determines that a shock is required, it will deliver the shock itself.

All defibrillators are safe to be used by anyone, as they will only ever administer a shock if one is required. For this reason, a fully automatic AED can be more advantageous in environments where a responder may feel hesitant, as any delay in pressing the shock button reduces the patient's survival chances.

Is it a good idea to have a defibrillator?

Having a defibrillator will mean that you are more likely to be able to save the life of someone experiencing a cardiac arrest. There are no negatives to having an AED.

As mentioned above, AEDs will only shock people with “shockable” hearth rhythms. If someone’s heart rhythm is shockable, they will not survive without the quick use of a defibrillator, so providing and using one equates to choosing to give that person a chance of survival.

Read this blog if you are considering whether to get an AED for your workplace.

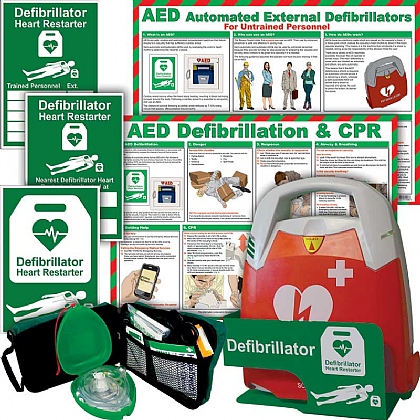

Below are some of our best-selling AED’s or you can take a look at our full range here:

Don’t forget, upkeep is as important as the original purchase. Your AED will inform you when you need more supplies, but it is always a good idea to have spare pads – for adults and children – available, as well as staying aware of the battery power.

AEDs are an investment and, of course, you will want to take care of yours. Brackets are a great choice to make your AED visible and accessible, particularly if you can put supportive guidance around them. For a more secure option in a public or outdoor setting, a cabinet may be preferable.

If you choose to have a defibrillator, registering it with initiatives such as The Circuit or GoodSAM makes it accessible to even more people, and therefore even more likely to save lives.

The more AEDs there are across the country, the higher the chance of survival rate for cardiac arrests.